Any philosopher with even the most rudimentary insight into the human

social dynamic should regard the rebranding of the Pan-American Union

with alarm. Once again, humanity has failed to learn its lesson and

willingly shackles itself to the same disastrous fate from which it has

only recently emerged. The folly, then and now, is not some strategic

slip-up or a misguided ideology; the fault lies in a source far more

subtle and pervasive, the very paradigm through which society is

organized. That the world has been slowly and steadily marching toward

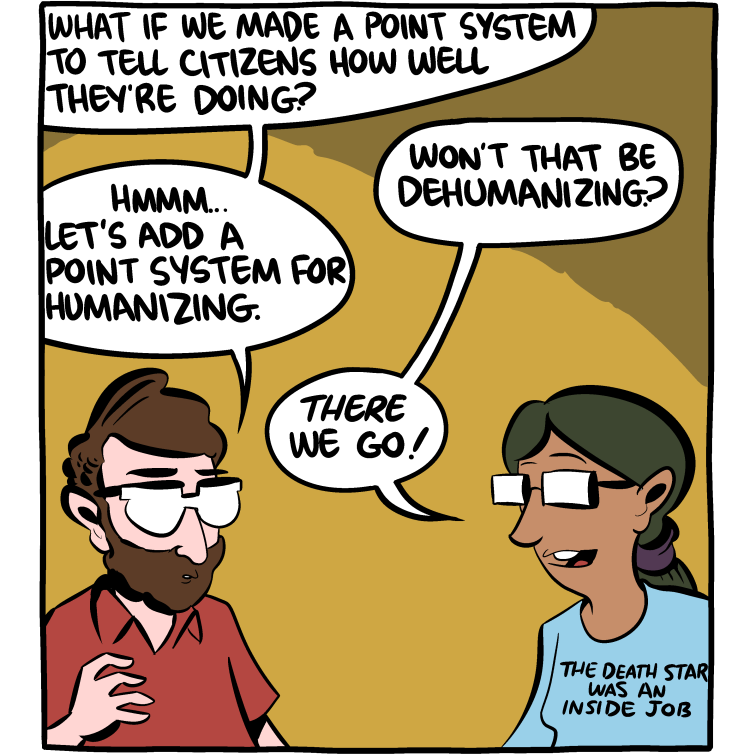

dehumanizing technocracy is, as recent history can attest, a fact. But

North America’s willing embrace of this doctrine has been conducted with

such audacity that even staunch positivists react with skepticism and

suspicion.

The term ‘technocracy’, literally, ‘rule by the technicians’, is in the

strictest interpretation a cross between the medieval guild system and

meritocracy. This semantic is only really of interest to historians and

linguists, with common usage tongue-in-cheek to describe a society

governed by disinterested and/or self-righteous scientists. Only in the

past few decades has it (re)gained traction in the vernacular as a

theory of government in its own right, with America the first

self-proclaimed technocratic state. But while this modern technocracy

does share its philosophical genealogy with its literal Greek reading,

its actual manifestation is far more sinister than even the cynics

imagine. It is not merely that the public is being conditioned to trust

the specialists on the basis of credentials alone; these specialists, in

turn, have invested blind faith into the dangerous delusion that their

cause is a self-evident truth, that they are merely playing out their

preordained role in the great machine that is linear historical

progress. What Texark touts as the utopian transcendence of ideology is

neither apolitical nor utopian: it is itself an ideology—admittedly a

seductive one—that is inherently oppressive, exploitative, and utterly

contemptuous of the very faculty it purports to promote.

Plato and Aristotle presupposed the universe to have a purpose. GWF

Hegel presupposed the state to be the ultimate expression of a nation’s

freedom, and a universal homogeneous State to be that same freedom writ

large. No matter the doctrinal differences, every theology takes for

granted the beauty and perfection of singularity. To question otherwise

is to throw one’s lot in with the Luddite, the barbarian, the

irrational. And it is precisely this presupposition’s

astounding ability to stifle serious debate that proves the Technocracy

illegitimate. We are told that we must trust Science, not because it is

inherently good, not even because it is demonstrably good, but simply on

the virtue that it is Science. We are told that we can trust Science

implicity, because its cornerstone is Reason, and what

civilized person would dare contest humanity’s most ubiquitous faculty?

Yet we must not forget that the Science that is reclaiming the

irradiated wastes is the same Science that built the bombs that

irradiated them in the first place. The Science that feeds three-fourths

of the world can, as demonstrated by Indonesia in 2106 and 2113, also

starve it in an instant. “Trust in progress,” says Texarkana,

proclaiming its virtues and denying outright that its progress can ever

be fallible.

Of course science is important, and of course so long as humanity is

imbued with the dual faculties of reason and curiosity, the march of

progress shall continue. Particularly in this post-apocalyptic world,

where thousands of acres of land in what was once the cradle of

civilization are now utterly uninhabitable, where billions of people do

not know the taste of naturally-grown food, the very survival not only

of our species, but of the entire planetary biosphere depends

on technology. But just as even the most self-assured general cannot

command his battalion across a gaping chasm without expecting his men to

fall to their deaths, so too the so-called specialists cannot mold the

world to their ideal simply by ignoring inconvenient truths. The pursuit

of science is still as valid and noble as it has ever been, and it is

therefore so imperative that the Technocracy be exposed for the

anti-scientific charlatan it is. The scientific inquiry has been

bastardized; a philosophy rooted in the principle of doubt, of

challenge, of always and ever questioning, has been twisted

into a prescriptive dogma of obedience. A regime that claims to embody

the pinnacle of Western progressivist thought is in fact the shrewdest

implementation of its polar opposite.

Science itself is not democratic. Factual validity does not

lend itself to majority opinion. The pursuit of science, however,

demands a democratic thinking space. Only through the freedom

to inquire, to debate, to experiment, are theories proven or debunked

and the truth revealed. It is therefore essential that whatever its

political implications, science remain apolitical and the scientific

community maintain a healthy distance from the power brokers. Here is

the first great danger of the Technocracy, for it foments an incestuous

relationship between Science and the State. It is one thing for a

government to sponsor scientific development; but when absorbed into the

state apparatus so completely, the notion that science will remain

neutral quickly becomes absurd. Whenever anything becomes

institutionalized, it grows rife with conservatism, cronyism, and

dogmatism; even outside of the collusive North American context, the war

between the legitimating journal and the lowly field scientist rages

each and every day. How much deeper will the status quo be entrenched

once those ivory-tower bureaucrats are vested with full state power? How

vulnerable will dissenting voices become? A century and a half ago the

world ridiculed those countries that sought to veto scientific theories

on the basis of ideology; but when science is that ideology,

who will be brave enough to decry the emperor’s nudity?

The second great danger of the Technocracy is that it subordinates

Science to Technology. This is not merely an issue of government policy,

but the very heart of the technocratic paradigm. Humanity presupposes

that technology is a tool it has designed, a force multiplier,

an aid. And it is. But technology brings with it a way of

thinking, a deeply materialist and utilitarian ethic of which few

are even conscious and even fewer take for anything other than granted.

What is technology, but a means of increasing efficiency? Inventions are

appraised based on their immediate usefulness: if it runs longer, works

harder, moves faster, it is marketed, adopted, becomes a life essential.

Luxury translates into basic necessity; the standard of productivity

rises; greater efficiency is demanded and new inventions are needed, and

the cycle continues. It should hardly be surprising that even the most

politically repressive regimes follow free market economies, as these

provide the most efficient means of wealth generation and resource

extraction. The most important feature of this paradigm is that it pays

absolutely no regard to ethics, except those which fit within

the technocratic frame: everything, from material production to

environmental conservation to human relations, is calculated on a

ruthless cost-benefit analysis. It is more efficient to

outsource to sweatshops than pay a living wage. It is more

efficient to slaughter an enemy village wholesale than contend

with political dissidents. It is more efficient to remove the

legislature, executive, and judiciary from public oversight than face

demoralizing protests, costly court battles and needless procedural

roadblocks over outdated religious morality.

This is the third great danger of the Technocracy: it redefines the

parameters of public debate and participation. The most fatal error the

concerned citizen can make at this juncture is to erroneously assume

that the question of efficiency has no political ramifications. Science

may have made Technology, but under the technocratic paradigm, and

especially under the conflict of interest that defines the Technocratic

Union, scientific inquiry will no longer concern itself with objective

truth, but serve as the legitimating lackey to the State agenda. Though

the state now brands itself a republican confederation, the regime put

in place by St. Louis remains unmitigated, if not stronger than ever,

the pretext of democracy a distraction from a tyranny more insidious

than the most craven totalitarian: one not affixed to any one leader,

party, or ideology, but the entire social psyche itself. It is a regime

predicated on manufacturing consent, not through showy propaganda, but

precisely through the perpetuation of an incontestible and

‘self-evident’ materialist faith that presents its twisted vision of

science and reason as uncontested truths. At the same time it purports

to establish a new status quo based on objective fact, it is

concentrating decision-making power within the hands of an exclusive

clique that unlike elected representatives is removed from public

scrutiny. This clique is governed by a pure cost-benefit ethic under

which everything, including human lives, is mere standing-reserve, free

to be exploited by and for whatever means most efficiently serve the

interest of the State.

Contrary to its self-conceived image, the Technocratic Union does not

represent a substantial break from traditional ideologically-driven

politics. It does, however, constitute an important paradigm shift in

political discourse, but one that should be read with extreme

skepticism. While it claims to embody the highest virtues of science and

reason, in practice it has corrupted the very essence of scientific

inquiry through a ruthlessly antidemocratic philosophy of utilitarian

materialism. But the Texark folly must not be mistaken for a purely

North American phenomenon: it is merely the most cognizant demonstration

of a philosophy that despite precipitating the calamitous world war has

lurked uncontested for at least two hundred years. Scientists of the

Twentieth Century made the atomic bomb, but the State deployed it; under

the Technocracy, the scientists will deploy it, without reservation. If

Hegel was right and the Technocracy is all the cunning of Reason, then

perhaps rationality is not the magnanimous benefactor that we have

presupposed.

On Technocracy by @Thorvald (El Thorvaldo)

This miniature essay was originally written as roleplay for Imperium Offtopicum XIV, and includes minor textual revisions and typographic corrections. It draws strongly from Martin Heidegger's 1954 essay "The Question Concerning Technology", and can be summarized as Heidegger dumbed down for the IOT crowd. Although written in the context of the game and under a tight deadline (one, maybe two days' spare time), I think it's sturdy enough in its address of the general issue that I submit it here. It certainly sums up my thoughts on the matter, and why I shudder every time a player calls their country a 'technocracy'.

The in-game context in which this was written concerned a shadow war between my country, the United Arab Republic, and the Pan-American (later Technocratic) Union, a similar joint state that at the time was under sole control of Sonereal, and against whom I'd been at war since it invaded the Northwestern American Union in 2106. While Sone unilaterally declared the war over in 2112, he refused to negotiate a treaty and for all intents and purposes everyone else treated it as still on. With Thai aggression in Indonesia and the Russian invasion of Rome, I wasn't in a fit state to deploy a full invasion force that far overseas, and after analyzing the state of American politics opted to try dismantling the country from within through dissident propaganda.

This piece was intended as a companion of sorts to an unpublished (and in fact incomplete) op-ed written from the explicit point of view of the UAR that I may finish and upload here at a later date; it followed a more conventional polemic published anonymously the turn previous, in which I attacked Mayor Francis and the Triumvirate in St. Louis on specific charges. Sone got wind that foreign agents were behind the agitation and attempted to pre-empt me by redividing the Union that turn, not realizing that was my goal all along. The turn for which this was written was scrapped as the game was abruptly cancelled, but judging by the world map released in debriefing, my pseudo-intellectual diatribe had shattered Sone's projected two-state solution into five, plus a conflict within his own partition plan.

In other words,

I OUT-SCHEMED SONEREAL!!

Comments & Critiques (0)

Preferred comment/critique type for this content: Any Kind

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in and have an Active account to leave a comment.

Please, login or sign up for an account.